Early Life

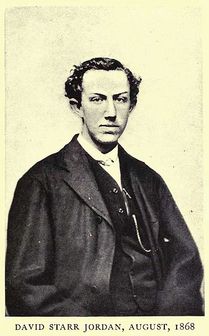

David Starr Jordan was born on January 19, 1851 in Gainesville, New York. Like other prominent American leaders during the late 19th century and early 20th century, Jordan came from humble beginnings and grew up on a farm attending a rural district school until the age of 14. His parents Hiram and Huldah Hawley Jordan were of English Puritan origins. Jordan was very aware of the virtues and blood lines of his ancestors and describes them intensely in his memoirs The Days of a Man, published in 1922. For example, he describes his mother as "a woman of large stature ad strong religious character, though liberal as to the details of faith, she had a distinctly original mind, a broad outlook on affairs, considerable native literary skill, and (for her time) a good English education" (#1 p.1-2) It is easy to see that Jordan looked back on his family in terms of heritable factors, using terms such as "native" and "stature." His father had a strong sense of duty and virtue as a staunch abolitionist and crusader against liquor. From these Puritan ancestors, Jordan was ingrained with virtues that would help guide his decisions later, especially with regards to his efforts for world peace in his late life. Jordan's early religious exposure was through his father, who was an equal supporter of both the Unitarian and Universalist religions. While Jordan never committed himself to a religion, the beliefs of these two organizations helped Jordan to formulate his views on religion later in life.

At the age of 14, Jordan enrolled in Gainesville Female Seminary and was one of the few men ever admitted to the institution. After receiving an education in French, algebra, geometry, history, and English he decided to turn towards teaching, at the young age of 17. He taught in an elementary school in South Warsaw, a rough industrial hamlet. In 1869, Jordan won a scholarship and was admitted to Cornell University. While he already had a strong educational foundation, it was only in Cornell where he would discover his love of science.

At the age of 14, Jordan enrolled in Gainesville Female Seminary and was one of the few men ever admitted to the institution. After receiving an education in French, algebra, geometry, history, and English he decided to turn towards teaching, at the young age of 17. He taught in an elementary school in South Warsaw, a rough industrial hamlet. In 1869, Jordan won a scholarship and was admitted to Cornell University. While he already had a strong educational foundation, it was only in Cornell where he would discover his love of science.

Formal Education and Early Educational Career

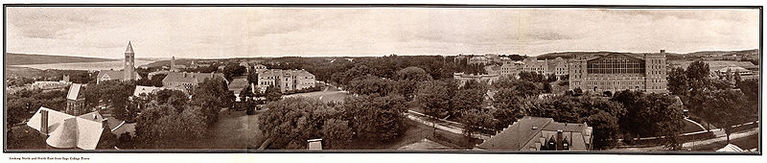

Cornell University circa 1919

Jordan studied botany at Cornell and completed so much coursework by the year of his graduation that he was awarded a Master of Science in 1872. He worked his way through school, holding a number of jobs from farming to janitorial work to waiting tables. He was finally appointed as an instructor in his junior year based on his impeccable academic record. While his primary focus was in botany, Jordan explored a number of other interests including literature, history, and foreign languages. He was elected Class Essayist , Class President, and Class Poet during his tenure at Cornell. He showed an affinity for leadership and persuasion even during his early college career.

Upon graduation, Jordan continued to pursue a career in education. His early appointments included Professor of Natural Science at Lombard University in Galesburg, Illinois, Principal of the Appleton Collegiate Institute in Wisconsin, and a natural science teacher for an Indianapolis High School. Between school years, Jordan conducted research on marine botany and fish in nearby lakes and rivers. While in Massachusetts studying under Agassiz (see below), he met his wife, Susan Bowen, a graduate of Mount Holyoke college. After one year of studies at Indiana Medical College, he received a Doctor of Medicine. Jordan recalls, "it had not at all been my intention to enter that profession. A certain amount of medical knowledge, I thought, would enable me to teach Physiology better" (#1 p. 146) He then taught at the Harvard Summer School of Geology and then at Butler University as a Professor of Biology.

Upon graduation, Jordan continued to pursue a career in education. His early appointments included Professor of Natural Science at Lombard University in Galesburg, Illinois, Principal of the Appleton Collegiate Institute in Wisconsin, and a natural science teacher for an Indianapolis High School. Between school years, Jordan conducted research on marine botany and fish in nearby lakes and rivers. While in Massachusetts studying under Agassiz (see below), he met his wife, Susan Bowen, a graduate of Mount Holyoke college. After one year of studies at Indiana Medical College, he received a Doctor of Medicine. Jordan recalls, "it had not at all been my intention to enter that profession. A certain amount of medical knowledge, I thought, would enable me to teach Physiology better" (#1 p. 146) He then taught at the Harvard Summer School of Geology and then at Butler University as a Professor of Biology.

Education from Louis Agassiz and Acceptance of Evolutionary Theory

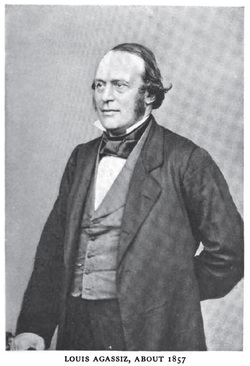

In 1873, David Starr Jordan was among the fifty science educators invited to attend the Summer School of Science hosted by Louis Agassiz on the island of Pekinese off the coast of Massachusetts. His summers at this school profoundly affected him. Quotes from Agassiz permeate the entirety of Jordan's published works.

Agassiz believed in the coeducation of men and women and people criticized him for including fifteen women in his original fifty pupils. However as Jordan notes in his memoirs, "his thought was that those 50 teachers, women as well as men, should be trained in the right methods, and so carry back into their own schools sound ideas on the teaching of science." (#1 p. 109) Agassiz believed in a hands on science education, complete with work in the laboratory and field, a novel idea at the time. Despite his progressive ideas in education, Agassiz did not believe in Darwinism due to his strong religious emphasis. Instead, he thought that his studies of animal and plant life were "glimpses into the divine plans of which their structures are the expression" (p. 115.) Agassiz also believed in the freedom of science, and encouraged his pupils to adopt any beliefs that they felt strongly towards.

Therefore, David Starr Jordan first accepted Darwin and his theory of evolution during these summers on the Pekinese island. It was not through the persuasion of others, but rather through his own serious studies in Zoology that led Jordan to become an evolutionist.

"Gradually I found it impossible to believe that the different kinds of animals and plants had been separately created in their present forms. Nevertheless, while I paid tribute to Darwin's marvelous insight, I was finally converted to the theory of divergence through Natural Selection and other factors not by his arguments, but rather by the special facts unrolling themselves before my own eyes, the rational meaning of which he had plainly indicated. All of Agassiz's students passed through a similar experience, and most of them came to recognize that in the production of every species at least four elements were involved: these being the resident or internal factors of heredity and variation, and the external or environmental ones of selection and segregation" (#1 p. 116)

These elementary ideas regarding Darwin's theory would permeate the rest of David Starr Jordan's life. Divergence through Natural Selection was not only applicable to his work in biology, but would also apply to Jordan's outward promotion of the eugenics movement and his highly developed social ideas as well. Agassiz died in December of 1873 and although Jordan returned to the Summer School the following year, it did not have the same impact on him without its progressive leader.

Agassiz believed in the coeducation of men and women and people criticized him for including fifteen women in his original fifty pupils. However as Jordan notes in his memoirs, "his thought was that those 50 teachers, women as well as men, should be trained in the right methods, and so carry back into their own schools sound ideas on the teaching of science." (#1 p. 109) Agassiz believed in a hands on science education, complete with work in the laboratory and field, a novel idea at the time. Despite his progressive ideas in education, Agassiz did not believe in Darwinism due to his strong religious emphasis. Instead, he thought that his studies of animal and plant life were "glimpses into the divine plans of which their structures are the expression" (p. 115.) Agassiz also believed in the freedom of science, and encouraged his pupils to adopt any beliefs that they felt strongly towards.

Therefore, David Starr Jordan first accepted Darwin and his theory of evolution during these summers on the Pekinese island. It was not through the persuasion of others, but rather through his own serious studies in Zoology that led Jordan to become an evolutionist.

"Gradually I found it impossible to believe that the different kinds of animals and plants had been separately created in their present forms. Nevertheless, while I paid tribute to Darwin's marvelous insight, I was finally converted to the theory of divergence through Natural Selection and other factors not by his arguments, but rather by the special facts unrolling themselves before my own eyes, the rational meaning of which he had plainly indicated. All of Agassiz's students passed through a similar experience, and most of them came to recognize that in the production of every species at least four elements were involved: these being the resident or internal factors of heredity and variation, and the external or environmental ones of selection and segregation" (#1 p. 116)

These elementary ideas regarding Darwin's theory would permeate the rest of David Starr Jordan's life. Divergence through Natural Selection was not only applicable to his work in biology, but would also apply to Jordan's outward promotion of the eugenics movement and his highly developed social ideas as well. Agassiz died in December of 1873 and although Jordan returned to the Summer School the following year, it did not have the same impact on him without its progressive leader.

Indiana University

Following his stint at Butler, Indiana University offered Jordan a professorship of Natural History in 1879. He then spent the next five years teaching zoology, botany, physiology, and geology. At this time the Board of Trustees unanimously elected David Starr Jordan as President of Indiana University even though he did not have much experience in educational leadership. His colleagues recognized Jordan for his zeal and enthusiasm for research and education even at the young age of thirty-five.

At the time Jordan was elected President, Indiana University was not regarded as a respectable state university. Its largest academic department also served as the local high school, preparing students for college. Alumni and state support were minimal and there was a strong group of people who wanted to close the institution altogether.

Jordan completely revamped the curriculum in 1886 to include two years of general education followed by another two years dedicated to a particular specialty or "major." Each student was also assigned a "major professor" who would counsel and assist the student in this subject.

At the time Jordan was elected President, Indiana University was not regarded as a respectable state university. Its largest academic department also served as the local high school, preparing students for college. Alumni and state support were minimal and there was a strong group of people who wanted to close the institution altogether.

Jordan completely revamped the curriculum in 1886 to include two years of general education followed by another two years dedicated to a particular specialty or "major." Each student was also assigned a "major professor" who would counsel and assist the student in this subject.

Personal Life

While at Indiana, his wife of ten years Susan Bowen died in 1888 followed by the death of his youngest daughter in 1889. Edith and Harold, his two other children, survived to adulthood. Jordan's father also passed in 1888.

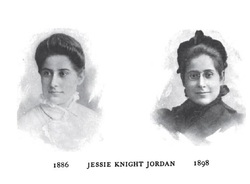

Jordan remarried to Jessie Knight shortly after the death of his father in 1888. His memoirs also delineate the heritage of Jessie, demonstrating his interest in maintaining the integrity of his bloodline.

"Miss Knight was the daughter of Charles Sanford Knight, a veteran of the civil war, and Cordelia Cutter Knight both formerly of Ware, Massachusetts. On Mr. Knight's side, there was a dash of French Huguenot blood which shows itself plainly in olive complexion, dark hair, and big black eyes of his children, persistent through succeeding generations." (#1. p. 326)

Jordan remarried to Jessie Knight shortly after the death of his father in 1888. His memoirs also delineate the heritage of Jessie, demonstrating his interest in maintaining the integrity of his bloodline.

"Miss Knight was the daughter of Charles Sanford Knight, a veteran of the civil war, and Cordelia Cutter Knight both formerly of Ware, Massachusetts. On Mr. Knight's side, there was a dash of French Huguenot blood which shows itself plainly in olive complexion, dark hair, and big black eyes of his children, persistent through succeeding generations." (#1. p. 326)

Jordan had two more children with Knight, named Barbara and Eric. At one point he composed a poem for his daughter Barbara called A Study in Heredity. "For in it I sought to trace the origin of the black eyes she had inherited form her mother and grandmother Knight, but which, I felt sure, must have descended from a racial source outside of or back of my wife's New England ancestry" (#1. p. 530) Even when entertaining his child, Jordan turned towards science and heredity.